The discussions on storytelling and emotions in video games, especially that around its inherent value, seem to be centered around whether interactivity seems to, somehow, lessen the value of such kind of fiction. Still, as early as the mid-60s, interactive fiction emerged as one of the earliest forms of gaming, going on to enjoy great success in the following decades. Thus, assuming every kind of “written storytelling” as an art form, even the arguable less noble expressions, it would be only logical to include “interactive” as part of the same brethren, with adventure games a natural prosecution of that very same interactive fiction genre.

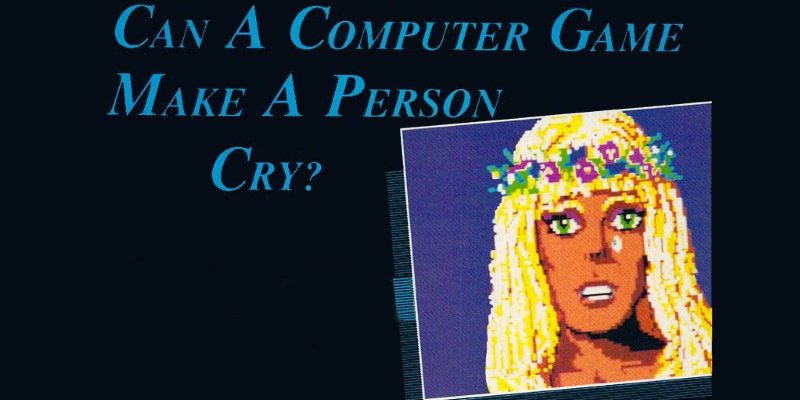

It was actually one of those adventure games that asked that neverending question, as related by Sierra’s 1988 ad for King’s Quest IV. But, even as late as 2013, it seemed the question was still relevant: “can a videogame make you and another human experience an emotion that’s deep enough to touch adults“? Apparently, it was considered “weird” for a crowd of computer gaming enthusiasts to be tearful in front of a videogame. It would be interesting to see if a similar discussion emerged, in the early 20th century, when movies became more and more complex featuring dramatic twists and turns, such as Robert Wiene’s Orlacs Hände (1924) or Ernst Lubitsch’s exquisite melodrama Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925). Was the public surprised or were critics taken aback by finding themselves in tears in front of something as trivial as “a movie”?

There is a substory in Yakuza: Like a Dragon (2020), a 5 minutes narrative, where the protagonist Ichiban runs into a bunch of trash on the streets. He discovers that it belongs to a headstrong pawnshop owner who has no intention of cleaning up, despite the authorities and neighbors’ complaints. A fight ensues (it is Yakuza, after all): after being beaten down, the owner breaks down in tears while recounting that the trash is all memories of his wife, left behind after she died while working long hours to support his frivolous lifestyle.

It’s a short vignette, one not even particularly celebrated in the history of the series, mostly remembered for the abundance of off-the-wall characters and situations (there is little contest when the same game features yakuza members in diapers). Still, I found myself in tears while listening to the story of the pawnshop owner who hangs on to the memories of his wife because it’s all he’s got to go on. The obvious answer to the question, about games and their power to make the player emotional. There really should be no surprise nor shame in crying in front of a game, as there isn’t anymore for a book or movie.

But, is the comparison between emotions in passive vs interactive storytelling really a fair one?

As the medium embraced more and more complex narratives in recent years, games – especially those belonging to the “mainstream” market segment – seemed to embrace their new role as a modern manifestation of the classic (and today, definitely less relevant) blockbuster Hollywood product. Referring, in particular, to that period in the 90s when movies were apparently being judged on the magnitude of their budgets. Not a year went by that a new movie would be marketed with the tagline “the most expensive movie produced yet!”. Still, AAA status has, obviously, nothing to do with the emotional power of a product. The competency of games to emotionally move the player definitely correlates to how public perception towards interactive storytelling has mostly changed over the years.

The role of the narrative designer has also become central in development, as opposed to that of a generic scriptwriter. Perhaps, then, it can be assumed that the ability to emotionally move the player should be inherent to how video games function at their core. “Emotions”, in interactive fiction as a medium, has become the terrain where game design and writing should converge.

Ruins of the Moon & NieR: tears in jRPGs

In Namco and Tri-Crescendo’s Wii-exclusive aRPG, Fragile Dreams – Farewell Ruins of the Moon, emotions were a big part of how memorable the experience as a whole felt. The post-apocalyptic scenario was specially designed in order to evoke feelings of loss and distant memories of things that used to be beautiful, now left in ruins. This emotional journey was easy to appreciate, despite gameplay that seemed to offer little of interest compared to other action RPGs of the time.

The design featured a small, but important, detail: the player carefully explored the dilapidated spaces while waving a flashlight, via Wiimote, in unison with the main character. While it all might have felt a bit too much at times – despite jRPGs being notorious for pushing on the touching side of the stories – Fragile Dreams felt like the perfect conduct for being cradled by one’s emotions and letting tears do their work. Would it have been the same experience without the, honestly, unnecessary motion controls?

Back when I played the RPG, I was in a weird stage of my life: caught between two relationships, one ending and the other beginning. Desperately, I was trying to hold on to the memories of the first, too stubborn to let go, while also being curiously afraid of what might come from the second. Naturally, Fragile Dreams didn’t help in making any kind of radical life-changing decision: as a substitute for a psychiatrist, it would be a pretty poor one.

But the RPG granted me a rare – in console gaming of the time – somber space to reflect and draw a breath, while also being surrounded by all these different strong emotions. It felt like finally being accepted for the imperfect being I was. Despite videogames always being identified as the perfect “escape” from one’s troubles and problems, Fragile Dreams felt like the opposite was true: I was there to face my problems, while making my way through an obscure path (while also not being far from “the middle of the journey of our life“) via the aforementioned waving of the flashlight. It is – perhaps – no surprise that I haven’t gone back to the game since.

NieR, as a jRPG experience, is also one worth mentioning. As opposed to most other titles in the genre, Yoko Taro’s RPG was unique in how its storytelling was spread among different genres: at one point, even going as far as becoming a full visual novel. Taro’s approach seemed to put gameplay in the background, with storytelling at the center of the overall experience: NieR was designed around the stories Yoko Taro wanted to tell, rather than the opposite.

While its overall design as an action RPG was – arguably – not completely successful, with many secondary stories being little more than timewasters, as far as jRPGs go, I would personally consider it one of the more interesting approaches in designing interactive storytelling. The original NieR (Replicant) was released to lukewarm reviews in a time (2010) when the genre wasn’t really being appreciated for its mature storytelling and critics’ attention had taken a backseat. Interesting to note how its sequel, Automata, despite a similar narrative and overall action RPG gameplay mixed (to a lesser extent) with other genres, was met with universal acclaim seven years later.

Mental health patients and death

Another worth mention is a title I’ve featured on the blog pretty early on, Blackstone Chronicles. Despite being a graphical adventure, most exchanges the player has with the characters take place through static dialogue, the few actually interactive characters only shown in paintings. It is as close to a visual novel as a point’n’click first-person adventure could get, at least back in 1998. I would argue this conscious design decision is, probably, the main reason the emotional experience is still left intact, hinging on the strength of the voice acting and the haunting stories of torture and pain that took place within actual mental institutions back in the early 1900s.

If they had decided to go with animating realistic characters, well, it would probably be a game that no one would choose to revisit today. Animating realistic and poignant sequences like people relating memories of torture and suffering, in 1998, would have been feasible only with real actors. Even having the right budget to do that, it would have been quite the huge effort to make it right. The way Blackstone Chronicles brings the characters to life is – instead – judicious, directly connects with the player and left me shedding tears.

But still, it is a narrative that works because it hits the player with the reality of what happened, not realy because of its interactive nature (which is, in conversations, definitely limited).

Let us, then, take a look at the other end of the spectrum, an experience like What Remains of Edith Finch (sometimes referred with the vaguely derogatory term “walking simulator”) is one that would be impossible to replicate in a “non-interactive” medium. Giant Sparrow designed the gameplay, as a whole, as the main channel to communicate to the player the different personalities of the members of the “cursed” family of the story, along with how they felt in pivotal moments of their lives.

Experiencing the story is strictly connected to exploring every room in the house which, naturally, has been purposefully designed to express each of the characters’ uniqueness: taking a look (not even interacting per se) and poking around is essential in getting awashed into the story and its emotions. A beautiful example of that design is how the developers narrated the episode of the older brother of the protagonist: trapped in a repetitive job, while also daydreaming of distant lands and a different fate.

The character’s own experience is brought to the player by juxtaposing the repetitive nature of the cannery work (pick up fish, cut head, throw the body with the others) with an embryonic action/adventure RPG that needs to be played at the same time. The example encapsulates perfectly the uniqueness of “interactive fiction”: the player really feels, via their hands, the terrible and crushing boredom of a repetitive work experience while also lifting up one’s spirits with exploring this new fascinating dreamworld. Unfortunately, there is that one final price to pay.

It is a sequence that is not only narrated via voiceover, which would still work on its own perhaps, but the whole experience is strictly connected with the face that we’ve experienced that for ourselves. The player will be shedding tears by the end of Edith Finch’ story because we’ve seen and experienced – first hand – how the curse of the family ended up affecting everyone’s lives and brought us to where we are, lost, but ready to begin anew with our newfound knowledge. Getting to grips with that emotional baggage takes time and curiosity to explore: it is not a merely passive interaction, but an active experience.

Another memorable experience – again by the same developers – that seem to uniquely work in its own interactive fiction space is The Unfinished Swan. Featuring precious little in terms of direct writing, the overall light narrative arch is expertly interwoven with its simple, but deep, gameplay mechanics. Designed like a stroll through an ancient storybook, the player moves the main character through several locations, starting from a completely white location (or palette) to places that feature more and more details. Its main gameplay mechanic of throwing paint to make the world come to life is used to connect to the overall narrative theme to “finish” things: giving life to what surrounds us or a purpose, a meaning. That same emotional message could be related via voiceover or, perhaps, an alternative story, but it would not really feel the same stripped of its gameplay mechanics and overall loose narrative structure.

Finding a common thread

The common thread running through all these different experiences hinges on the different interpretations of “interactive storytelling” and, especially, how the mechanics of game design affect the way such emotional content is related to the player. Writing and experiencing narrative in videogames, as opposed to books and movies, can be considered unique in this aspect. While interactivity is not required for an artistic product to elicit sadness in the “user”, I believe emotions in interactive storytelling feel more natural when videogames don’t just blindly follow the way cinema (or literary fiction) portrays emotions.

When discussions about “saddest games ever” pop up, Life is Strange and the first season of Telltale’s The Walking Dead are often mentioned. While it would be fair to agree that they didn’t hold back with their emotional punches along with featuring strongly well written characters, it is also noticeable how – outside of directly controlling the main character and making choices – the player is little more than a passive spectator of an episode of a TV show. The emotions mainly flow on the strength of the writing and the actors bringing the characters to life. This seems to suggest that both features could easily be translated into another non-interactive medium, little would be lost in their emotional connection with the audience.

Generally defining videogames as “interactive storytelling” could – in fact – be slightly misleading at times. When analyzing such experiences like The Last of Us or Assassin’s Creed, the narrative facets of such titles (which mainly revolve around cutscenes) seem to generally function on a completely detached plan from their strict gameplay/interactive experience. That is not to imply that their writing or emotional impact is, then, lessened, but it does highlight, though, the tendency, especially noticeable in AAA titles, to function on separate plans.

It is, then, perhaps no surprise that “movie” versions of these games appear frequently on YouTube racking up millions of views. These versions basically do away with the gameplay portions of the games, presenting only the narrative (or cutscenes). Do the emotions and characters still work? I’d reckon they do. Thus, we might ask ourselves a question: are the active controller holders experiencing the emotions, described in such titles, any differently compared to those, later, passive spectators of the cutscenes?

In 2021 it seems the overall discussion on interactive storytelling as a medium isn’t yet ready to fully embrace the – unthinkable – notion that crying can be as easily related to games as with other, more traditional, kind of fiction. Perhaps, because of how the infantile notion of “playing” is still so strongly connected to the general notion of “games”. In our overall consideration, the medium is still considered much too young and immature to be aiming at such superior and noble goals, to be considered for adults

Still, it is worth thinking about how the revered Montessori method of education reserves quite a noble role to the notion of “playing”: it is a child’s work. Growing up, the only change occurs in the games that we – as a society – choose to play: they still remain our main occupation, we still need to play to be stimulated, to remain involved and reminded of our role in society. Not to mention, the power of stories that – ever since the dawn of mankind – have helped us in coming to grips with our emotions and strenghthen our empathy and bond with others.

As weird as it would feel to advise someone to play Fragile Dreams to feel better in their daily struggles or check out What Remains of Edith Finch to invite to a poignant reflection on the meaning of family, it still would feel completely appropriate. Crying might also represent a moment of catharsis, cleansing oneself from negative emotions. The objective of these experiences in interactive storytelling seems to be just that, in the end: starting anew.

The intrinsic quality of being “interactive” is central to the way these experiences connect to emotions in video games and how they can bring us to our emotional breaking point, ready to be filled again with the next experiences that await. The player is tasked only with keeping a vulnerable state that invites shock, emotions and tears. Videogames have been around long enough to easily notice the changes in their language over the years: it would be appropriate for the gaming public at large to accept that. They mirror changes in our social structure, can portray conflicts or crises, inviting and stimulate discussions on matters of personal and gender identity. Also yes, indeed, they can make you break down in tears.

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to help me to keep the project running, be sure to check out my patreon or alternatively, offer me a coffee.

This was a really good read! I think you’re right that the question is asked for quite strange reasons, related to how “play” is seen as juvenile.

Part of the reason I struggle with this question is that I feel sadness and grief don’t easily go hand-in-hand with an interactive narrative. In a linear work, I often feel sad at the death of a character or a terrible event because the event cannot be overridden or changed: it’s the only possible outcome, so I have to wrestle with it. I don’t get that feeling of inevitability if I can reload an earlier save and undo the problem.

I think that’s why it’s easier to have a sad reaction to more linear game narratives (eg. Walking Dead, Edith Finch): even if their interactive elements definitely enhance the emotional experience, it’s not the narrative itself that’s interactive. I don’t feel a sense of profound loss if my character dies in Crusader Kings, for example, just disappointment: I can load the game and try to prevent that death, or start a new game and get a whole new character.

One solution to this problem that I’ve seen is where the loss is not inevitable, but it reveals something about the player, which evokes a sense of blame or responsibility. For example, in Mass Effect 2 I made some bad choices which resulted in Tali dying in the final mission. I felt responsibility for that death: had I been a better person, made better choices, it would not have happened. In that instance, I felt grief not for the loss of Tali (I could start a new game and save her, she wasn’t *gone*), but that my actions had caused something terrible. I think that by implicating the player in those sorts of decisions you can get more personal, but still interactive, causes of grief. Of course, they’re hard to design well because what makes one person feel implicated differs hugely from person to person.

You definitely bring up an interesting point, in that “interactive storytelling” also implies the possibility for the player to reload an earlier save and “try again” to save that character.

It cancels out that feeling of “definite” that death usually brings to our lives (or to a story, in this case).

I also don’t feel strongly towards permadeath one way or the other, cause I’ve never seen it used as a narrative medium: it might be interesting to see in the games you’ve mentioned or used in an overall action/adventure experience. For example, in a game like X-Com Terror from the Deep, one surely feels sad from the loss of an important member of the team, but it’s not because there was a narrative, but just because one invested a lot in the character and it is sad to see them go.

I think perhaps we could be investigating the consequences of “permachoices”, instad of permadeath. It would definitely be interesting from a game design perspective. I’ve seen a few games that featured them but none – until now – that seemed to use them in an interesting narrative perspective.

The sense of responsibility is indeed an important lesson to the player, as it was also showed in early non-narrative titles like Sim City where each player’s choice indeed might have brought to the player unforeseen consequences, which sure might be canceled by reloading an earlier save, but still remain clear in mind.