The evolution from Nirvana to Nirvana X-Rom begins… well, quite a few years before the release of the movie. Sweltering summer of ‘92. Italian director Gabriele Salvatores is shooting Puerto Escondido, together with actors Diego Abatantuono and Fabrizio Bentivoglio. Taking a break from the set, the three sit around a table for a quick match of Soccer on NES. As the game is finished, the console turned off, suddenly Diego turns and exclaims: “I wonder what happens when we turn off the TV, do the players wait patiently for our return? Do they go back to their girlfriends waiting at home?”. That throwaway joke will be the spark that shall lead Salvatores, four years later, to direct Nirvana.

On the other side of the screen, it all looks so easy

The idea to make a sci-fi movie in Italy, with a budget of around 5 million in today’s money, was very difficult for the producers to swallow, recalls the director. This despite the genre enjoying quite the great surge in popularity in the mid 90s, especially that sci-fi “cyberpunk” flavored, with titles like Johnny Mnemonic and Strange Days. The last real big budget sci-fi production from Italy would have been, probably, back in the mid 60s with La Decima Vittima (The Tenth Victim) by Elio Petri, starring Marcello Mastroianni. Salvatores mentions that, despite the producers’ initial resistance, he was still riding on the high of the Oscar won for Mediterraneo, back in 1991, so he could pretty much do what he wanted.

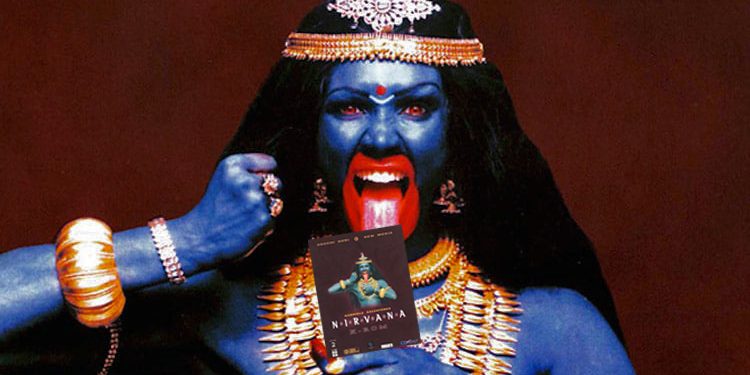

In the future (a mysterious 2010), overpopulated cities sit beyond skies heavy with industrial smog. Unhappy individuals pass the time by making heavy use of recreational drugs, while the economic system is dominated by greedy megacorporations. Well, isn’t that just so far removed from our reality? Jimi Dini (Christopher Lambert), a tribute to Hendrix by Salvatores, programmer for software developer Okosama Starr, is putting the final touches to his new virtual gaming experience: Nirvana. To work and interact with it, he uses a virtual reality contraption pretty similar to that seen in The Lawnmower Man, back in 1992.

While hunting down bugs, Dini discovers that the game’s protagonist, Solo (Abatantuono), has grown a conscience and is fed up with the endless cycle of dying, of game overs and having to start again from scratch. He wants to be free, thus he beckons Dini to finally delete the game and put an end to this ever perpetrating cycle of reincarnation. This is the beginning of Dini’s journey into the city’s underground, looking for someone who can help him penetrate Okosama’ servers to permanently delete all traces of the game from existence. In the course of his journey, he will also try to get back in contact with his former girlfriend, piecing together all the clues she left.

The movie is populated by several of Salvatores’ usual gang of friends, most of whom are notorious Italian comedic actors whose roles are so small that end up being little more than cameos. The big exception in the cast of Italian actors is, naturally, Christopher Lambert, who was apparently demanded by the production when the budget was inflated, in order to have someone that the international audience could recognize. While the movie is far from perfect, being especially dragged down by the half-baked sentimental sub plot, it presents an interesting melange of Eastern religions, cyberpunk subculture and a pinch of 90s gaming experience. That visual style was so effective that Salvatores is still asked to this day if The Matrix did not, in some way, “borrow” some of the elements from his movie.

Despite what one’s opinions of the movie, which seems to this day fairly divisive, Nirvana still stands as an important production, especially for the struggling Italian movie industry of the 90s. For the first time in history, digital special effects were produced in the country and many of those who worked on it, to this day, mention it as a very positive experience. But, most importantly for the sake of this article, it was the very first (and, unless I’m proven wrong, last) time that an Italian director specifically designed his movie to be released in parallel with a tie-in video game that would work as a direct sequel to the events narrated in said movie. That game is Nirvana X-Rom.

While it might be reasonable to doubt the artistic merits of such an idea, everything in the game connects to the original story and the Nirvana X-Rom title is even referenced a couple of times in the movie itself. Perhaps, Salvatores was honest in his intentions of seeing the natural prosecution of the story in video game form, but whatever the case, he seems to have, apparently, entirely forgotten about it over the years. The few instances when he’s talked about the movie, he seems to have never referenced X-Rom in any way. For all intents and purposes, while the movie is still somewhat remembered, especially by fans of the cyberpunk genre, the game (or rather, interactive experience) has all but fallen in between the cracks of history.

Let’s look at its development, specifically its original design.

Creating X-Rom - Making magic with a shoestring

The screenplay, or rather what we would today define as “game design”, was handled by Italian writer Bruno Tognolini, whom I spoke to via phone for the article. While Tognolini did not have the technological know-how of a game designer, surprisingly, he had actually worked on a videogame before. In 1994, he wrote the screenplay for an educational title, released on the Philips CD-i, for children’s show “L’Albero Azzurro” (The Light Blue Tree). Tognolini served for several years as a writer on the show, together with notorious children’s book writers Bianca Pitzorno and Roberto Piumini. Bruno tells me that he was directly approached by Salvatores, because the director had heard of his work on the CD-i and his experience with multimedia products. “He asked me to pitch a screenplay based on the movie’s story. I immediately thought of the idea of “the ghost in the machine”: when one uninstalls a program, even on Windows, there are always traces left in the computer. Nirvana, after being deleted by Dini, left traces on Dini’s computer, it is up to the player to delete them for good. Salvatores liked the idea and so I was on board.”

The overall look and feel of the game was based on similar first person adventure games of the time, with Myst being the first inspiration, with the idea of the player walking along “nodes” developed with Quicktime VR. But X-Rom was not really designed with the idea of being a Myst-clone, as Tognolini recalls, but something different. “I started working with the programmers from the CD Italy company, along with Salvatores’ Colorado movie. They gave me all the “b” footage they had, which was not used for the movie so that I could come up with gameplay ideas that could feel interesting for most players. For example, when the player has to get rid of the organ traders, I used a bit of the A footage from the movie, along with some unused B rolls. For that interactive sequence I decided to make their eyes red, so that the players could realize where to click to defeat them. I was conjuring up magic on a shoestring’s budget: trying to make everyone see the rabbit out of the hat trick, while equipped only with a hamster and a baseball cap.”

A big character in the game, as opposed to the movie where it only appears for a couple of scenes, is Jimi’s smart house. “I wanted it to be the first human-like interaction for the player, a reassuring presence for the first few puzzles. Then, for the rest of the game, the smart house would remain in the background as a sort of guide throughout the story, pointing the player in the right direction, but not really giving actual hints.” Several actors from the movie were contacted to reprise their roles for the short movie sequences. Stefania Rocca, who in the movie plays the hacker Nayma, acts as the real guide, dropping hints if the player gets stuck on a puzzle for too long. Along with her, Abatantuono also comes back as Solo. Tognolini remembers the shooting experience as peculiar: “they had built these very simple sets, using some of the original props, but again all very cheap. I particularly remember Diego Abatantuono because, when he came in, it was clear he had not even read the script. So he ended up improvising most of his lines based on his original role in the movie. He did pretty well, quite an expert actor.”

Designing X-Rom: from Cyberpunk to Children's Television

Referring back to his years-long experience with children’s television, Tognolini mentions that the writer’s objective was not simply to entertain the young spectator, but also keeping them busy. “We would not want to leave the child passively in front of the TV screen, but also stimulate their creativity as much as possible. So, for example, we would tell them to go fetch a jar of glue or a ribbon of a particular colour then compliment them for doing so. I thought that the very same style of interaction could also work for a video game. I did not want to just leave the player sitting on a chair in front of a screen, passively clicking away the hours. I thought the game could offer more than that.” Indeed, X-Rom features gameplay solutions that would surprise many players still today, so much so that they probably felt futuristic in 1996.

For example, at one point in the game the player is asked, by Solo himself, a passcode which is an actual phrase from the Carlo Collodi book, Pinocchio. Despite the book being pretty famous in Italy, Tognolini chose a phrase that is not really well-known, because his intentions were not about making it easy for the player. “I wanted the player to get up from the chair and go look for the book, perhaps around the house or even visit a public library to read it. I especially liked the idea of stimulating the player’s curiosity in the real world.” At another point, the game asks the player to insert a floppy disk to save a file on, but – curiously enough – X-Rom won’t allow you to read it back on the same computer one is playing on. Indeed, the player is advised (by the smart home) to seek out another computer, again relating to the “social interaction” that the writer was adamant to feature in X-Rom.

Naturally, the writer recalls that his peculiar gameplay design was not really appreciated by the producers or the programmers. “I remember at one point, one of Cecchi Gori’s (the movie’s producer -ed’s note) people called me and gave me a long lecture on how video games are supposed to be designed. He told me that video games are always supposed to be self-sufficient: the player does not have to go look around for hints in the real world, all solutions to the puzzles should be found in the gameplay and story. We do not want our players to get up from the chair, he went on. But I replied that my intentions were different from that of an ordinary game designer and, in the end, I managed to convince them to leave it as it is. I believe they did so mostly out of respect for my experience as a writer coming from a long experience of theater and television. Still, thinking back to it now, perhaps they were on the right track…”

True enough, the overall critical reception to X-Rom was lukewarm at best, with several magazines criticizing the puzzles’ high difficulty and many players having quite a hard time figuring them out. “In the final product there were several bugs as well, which obviously did not make things any easier. I did what I could to ease the players’ pain, I published on my website the entire solution (and screenplay) for the game as soon as I could. Still, even beyond my peculiar ideas, I think the greatest problem for the game’s commercial reception was the fact that it was designed, from day-one, to be strictly a tie-in product. If one had not seen the movie, Nirvana X-Rom provided no explanations or backstory of any kind. From the get-go, it had quite the small target audience.” While Salvatores did say Nirvana was a quite decent box office success in Christmas 1997, along with a good reception in the US, Nirvana X-Rom did not really follow suit, already ending up in the bargain bin by three months later.

Replaying X-Rom today is also no easy feat, since it requires an early version of Quicktime, so a virtual machine would be the best way to play it. Not mentioning the crashes that will still happen regardless of the platform. Still, its design is really one of a kind, feeling like a weird crossroad between a generic multimedia product, video game and “making of”, since the player can also access an archive of dialogues, still images and short sequences from Nirvana. But surely enough, thinking outside the box is required right from the start. The very first puzzle in the game will see the player having to answer four questions, all clues to the answers can be found in the introductory video sequence. A kind of punishment for whoever does not pay attention or usually skips them altogether!

The X-Rom aftermath

Tognolini still remembers the experience fondly and he’s glad to have taken part in what ended up being the last video game he would work on. “I actually had an idea for another game, but it was quite a complicated project. The story did touch on virtual reality again: there is this child playing a game, quite like The Sims, where he is making up this story of the voyage of Mary, Mother of Jesus, while she’s trying to reach Palestine while being haunted by a hitman. In real life, the child meets an artist who is working on a similar story by using statuettes in a nativity scene. The two then team up to try and save Mary from the hitman in the game. It wasn’t very far removed from what Ernest Cline did, later, with Ready Player One. I tried pitching the idea for a game to Cecchi Gori, or at least a movie, but was told my script was too dense and there was no way someone would want to work on adapting that for the screen. So, in the end, I decided to stick to the book format. While my original idea was to just call it “Palestine Quest”, in the end the editor decided to go for Lilim del Tramonto.” (Lilim of the sunset).

Twenty five years later X-Rom proudly stands as one of the most interesting experience in game design to come from Italy in the 90s. Its weirdly experimental character shines brightly, the way a writer managed to transmutate his experience outside the world of games into an adventure could be quite an inspiration for many designers still today, showing how a different field of expertise can still bring significant ideas to the table. In a similar way to a program that is uninstalled from a computer, but is never really gone for good, X-Rom left traces that still resonate throughout all these years for anyone out there that would like to listen. Tognolini is still playing adventure games to this day, he mentions he has been enjoying both What Remains of Edith Finch and Gone Home, he would be very happy if anyone would get to play them.

Thanks to Bruno Tognolini for the interview.

Thank you for reading.

If you would like to help me to keep the project running, be sure to check out my patreon or alternatively, offer me a coffee.

Wow, I remember this movie, never knew it had a game tie in.